In the 95F heat, jetlagged, and arriving in DC less than 24 hours prior, I cannot describe how happy I was to do a little jellyfish outreach with the interns and researchers of the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) Invertebrate Biology Aquaroom at the Annual Smithsonian Staff Picnic! Along with Dr. Allen Collins, Dr. Cheryl Ames, and interns Christine, Allison, Abby, and Daniel, we were showing off live jellies and preserved specimens to other Smithsonian researchers.

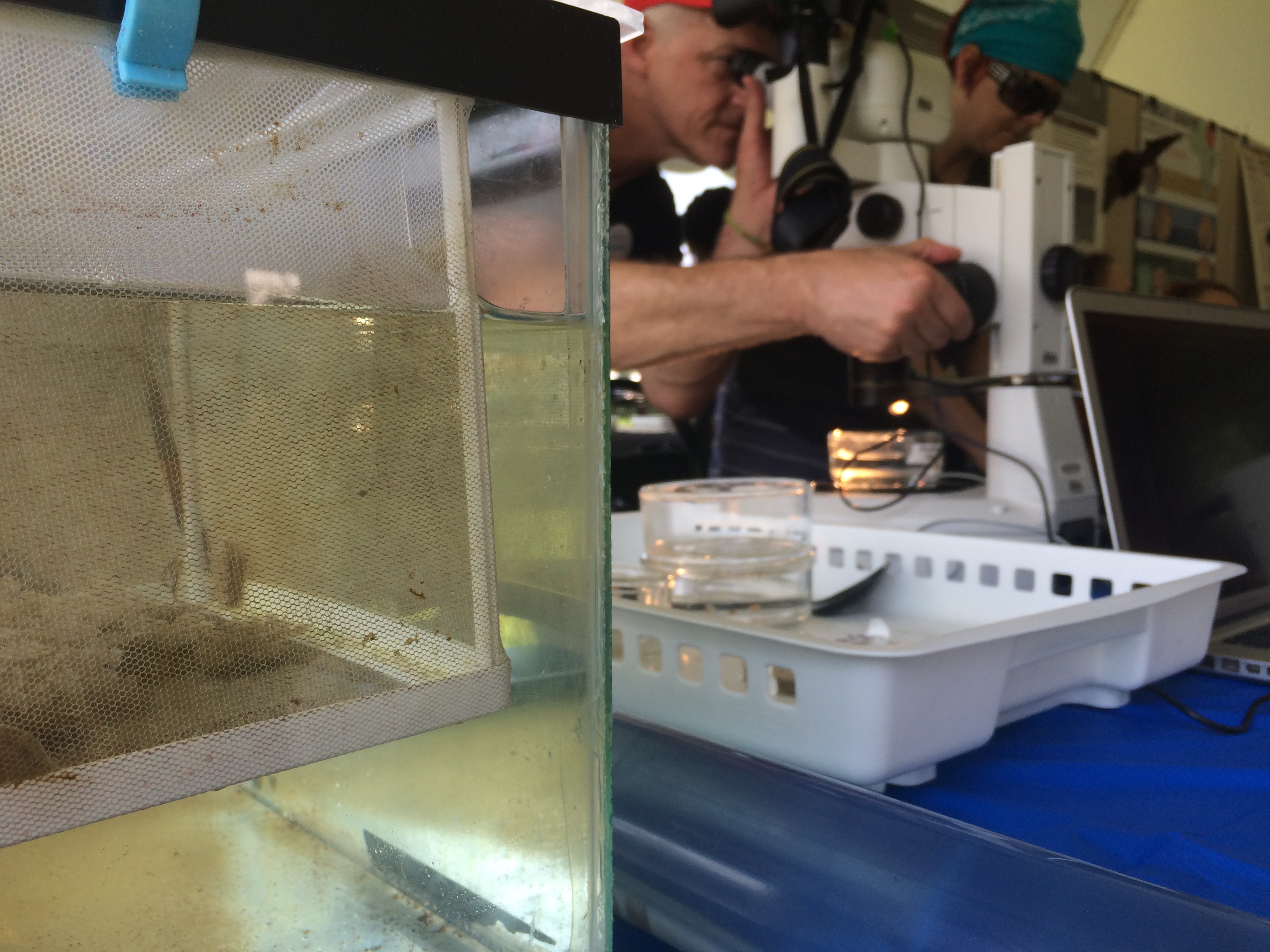

We had Upside-down jellies (Cassiopea xamachana) both in a tank and in a jelly wand, a clear, plastic pipe filled with saltwater used to carry jellyfish around (my science communication weapon of choice). There were dishes of Upside-down jellyfish and Moon jellyfish (Aureliasp.) polyps projected onto a screen through our microscope, and several jars of preserved specimens, including box jellyfish, a flower hat jellyfish, and stalked jellies (or staurozoans). Along with multiple posters on jellyfish taxonomy and stinging cells, and a custom banner made by Christine for the event, we carted the entire ensemble, literally on two carts, from the aquaroom to our tent at the edge of the Mall.

It was exactly the scicomm gig I needed to refresh from the hectic travel from the last few days. I enjoyed the time outside talking to people (even though it was super toasty), meeting everyone involved in the aquaroom, and reconnecting with Allen and Cheryl. Two years ago, I spent the summer working at the NMNH, which included a good chuck of that time in the aquaroom taking care of the upside-down jellies, box jellies, and the freshwater jelly, Craspedacusta. It feels great to be back, and I love seeing how much the aquaroom had grown! The four dishes of upside-down jellyfish polyps have expanded and grown to include over forty medusa spread throughout two tanks! The two petri dishes of box jellyfish polyps have expanded into multiple, dense dishes! And there so many more species housed in various glassware, incubators, and tanks all around the room, thanks to postdoc Dr. Rebecca Helm (see her work on her blog Jellyfish Biologist). The jelly wand had just been an idea when I was last here, and now I was using one to showcase our adorable Cassiopea to young children and veteran researchers alike. It was a great start!

Don’t just take my word for it, check out what Daniel had to say about the event!

Common questions:

- What species do you have at the NMNH?

In the aquaroom, there are currently 8+ species being raised, but Upside-down jellies are one of the most reliable for observing and maintaining the medusa stage. Most of our jellies are polyps, including moon jellyfish, freshwater jellyfish, box jellyfish, and sea nettles. We also have a large octocoral, which is the star of our larger tank.

- What are these animals used for?

Most of these animals are used for training interns on animal care and maintenance. They are also used in studies on animal development because of their complex life history. Several of the interns are extracting the DNA form various jellies to learn more about their evolutionary history, including phylogenetics, or how different species are evolutionarily related to one another. This is really important for taxonomy, or the classification of groups. Proper taxonomic classification ensures scientists understand each other across all disciplines. This can include splitting up groups into different species (see study on Chesapeake Bay sea nettle, Chrysaora chesapeakei) or classifying multiple species as the same (see study on Alatina alata). I am in the lab for a month working on Cassiopea and how they sting!

- Where do you find Cassiopea? And why are they upside down?

These jellies can be found all across the globe. They live in tropical climates that include seagrass beds, shallow, coastal areas, and, in the States, mangrove forests across Florida. C. xamachana (Order Rhizstomeae) specifically comes from the western hemisphere. Though there is some debate about the number of species; eight are currently accepted in the genus. Their abnormal benthic lifestyle is due to their need for constant and consistent light for their symbiotic dinoflagellates Symbiodinium, which live in their oral arms. This relationship provides most of the energy these jellies need to survive, though they still capture other animals for food using their stinging cells. We give our animal brine shrimp (sea monkeys) every few days to supplement their diet. These animals are still able to swim, though it appears to become more difficult the larger the medusae becomes.

- How old do jellyfish get?

We don’t know! In the lab we can reliably keep medusa for over a year, but it is unclear how long they live in the wild. For true jellyfish (Class Scyphozoa), the medusae stage tends to live for longer periods of time, whereas medusa in hydrozoans may only survive a week to a month. Polyps that asexually reproduce can technically live forever since they clone themselves on a regular basis (given good conditions), though it is not likely individuals or even the colony actually survive that long. Jellyfish geneticists will maintain the same animal strains to keep their research consistent between multiple labs, so these lucky few might be the longest living jellies!

- What do the different life stages of Cassiopea look like?

Actually, not a question we had because we had all these stages to show off! Below are some of the major life stages of Cassiopea.

- What are you using the ice packs along the tank for?

While our animals may be tropical, the change in temperature between outside and the temperature of the aquaroom is significant enough to cause some stress to the animals, so we are trying to keep them cool. Don’t worry, no animals were harmed in the education of the public!

References:

- Helm, R. JellyBiologist. Personal blog. Retrieved from https://jellybiologist.com/

- Daniel Jackson – Blog. (2018). Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/view/danielbjackson/blog

- Bayha, K. M., Collins, A. G., & Gaffney, P. M. (2017). Multigene phylogeny of the scyphozoan jellyfish family Pelagiidae reveals that the common US Atlantic sea nettle comprises two distinct species (Chrysaora quinquecirrha and C. chesapeakei). PeerJ, 5, e3863.

- Lawley, J. W., Ames, C. L., Bentlage, B., Yanagihara, A., Goodwill, R., Kayal, E., … & Collins, A. G. (2016). Box jellyfish Alatina alata has a circumtropical distribution. The Biological Bulletin, 231(2), 152-169.

- Ohdera, A. H., Abrams, M. J., Ames, C. L., Baker, D. M., Suescún-Bolívar, L. P., Collins, A. G., … & Jaimes-Becerra, A. (2018). Upside-Down but Headed in the Right Direction: Review of the Highly Versatile Cassiopea xamachana System. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 6, 35.

Fascinating!

LikeLike

Awesome!

LikeLike